Which Grasses Should You Plant in Your Pastures? Seed Selection for Pasture Renovation

As equestrians, we know that we must be somewhat selective of the mounts we choose. While exceptions exist, Quarter Horses tend to make better reiners than Saddlebreds, Warmbloods tend to make better jumpers than Arabians and Belgians tend to make better pullers than, well anything that isn’t a draft horse. It’s also no surprise that within each breed or discipline, some lines or family groups are just better at a specific skill then others. We like to think that selecting grass for our pastures is simpler, but the truth is, there are better species for different situations, and within each species, some varieties will perform better under certain conditions or geographical areas. Hopefully, this information will help you to select species and varieties of grasses for you fall planting.

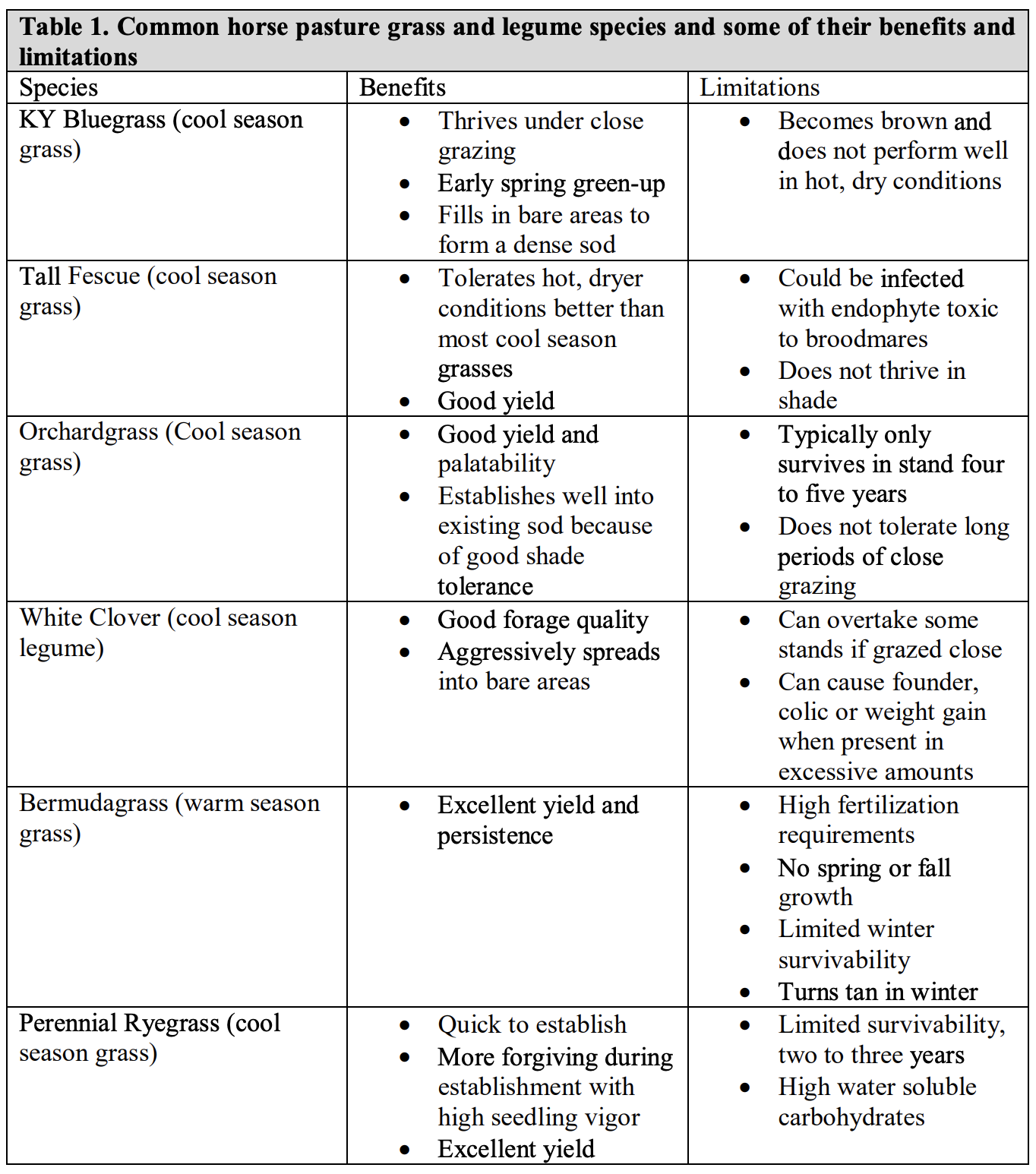

Species Selection

The biggest factor in selecting species is where in the country are you located, though use will also have some impact. Grass (and legume) species can be divided into warm season and cool season grasses. Warm seasons, such as bermudagrass and bahiagrass, thrive in warm climates, such as those found in the Deep South. Cool seasons, such as tall fescue and Kentucky bluegrass thrive best in the cooler northern regions. Kentucky and neighboring states are located in the transition zone, meaning that both warm and cool season grasses can be maintained, though cool seasons are the primary pasture grasses. Intended use can impact species selection as well and are best explained by example. The University of Kentucky Veterinary Science Department was interested in replanting a pasture that gets heavy use, but only in the summer months. For this reason, bermudagrass was recommended as it is high yielding and grazing tolerant and mainly productive in the summer months.

In another example, small paddocks that are usually grazed hard are often seeded with perennial ryegrass for its quick germination and inexpensive cost. Perennial ryegrass typically has the highest concentrations of water-soluble carbohydrates (WSC) of the cool season grasses, so some farms with overweight and/or founder-prone horses will decide against it.

Variety Selection

Like selecting an equine bloodline for racing or jumping, variety selection requires a bit of research, but pays off in the end. Seed can be of two types, “commercial” are those of improved varieties with known and proven genetics or “common,” seed that has unknown parentage and performance. Common may also be listed as “variety unknown or variety not stated.” This is equivalent to a “grade” in horses. With common seed, you may be getting a great variety, or you might be getting something that didn’t perform well or is mixed up with other seed. Common seed is often cheaper, but like buying horses, you get what you pay for. For this reason, we suggest only purchasing certified seed of a known variety and one adapted to your area and use.

Many universities, including UK, perform side-by-side comparisons of varieties to measure yield and persistence. In fact, UK has one of the largest forage variety testing programs in the country. Data from the trials is published annually in a series of reports and a summary report that can be found on the UK Forage Extension website (forages.ca.uky. edu).

In Table 6 of the 2019 Timothy and Kentucky Bluegrass Report, you’ll find the forage variety results of a comparison of five Kentucky Bluegrass varieties seeded in the fall of 2017. In this case, Maturity and Percent Stand were quite similar for most varieites. But the yield is where the differences lie, partiularly in the two-year total. Those that have a * after the number were not statistically different than the highest producing variety, in this case, Barderby. So Ginger performed as well as Barderby, but Balin, Park and Tirem did not. If yield is your sole focus, then one of these two would be the best variety for farms in the Lexington area. Keep in mind though this is only one test.

The 2019 Long-Term Summary of Kentucky Forage Varieity Trials combines data from tests from the last 30 years. Table 26 from this report shows the horse grazing tolerance of orchardgrass since 1999. For this table, the key is to look at the mean listed on the far right hand side of the table. Any number over 100 means that variety has performed better than average. The number in parenthesis tells you how many total tests that variety has been in, so give more favor to those with larger numbers because they have performed consistanctly over more time. For orchardgrass in Lexington, Benchmark Plus or Persist did best under horse grazing.

Choosing a proven variety backed by university data will give you confidence that you have choosen the most adapted variety available to your area and use.

Beware of “Horse Pasture Mixes”

Most agronomists will suggest you plant a mixture of grasses, instead of just one species. Quality mixtures are stronger because when weather and management become less favorable for one species, it likely will favor another. For example, Kentucky Bluegrass thrives in the cool, wet spring. But as conditions turn dry, tall fescue will outperform it.

It is tempting to take the easy and often cheaper option of pre-mixed “horse pasture mixes” available at many local farm stores. Before you purchase any of these, be sure to read the seed tag and see exactly what is in that mix. It could be a high quality mix, but there are too many examples that are more of a catchall of leftover seed. These may contain high amounts of timothy, an excellent horse hay but poor pasture grass. Or they may contain common seed or varieties that have not performed well in the area. Many contain high percentages of ryegrasses, which will provide some quick cover, but won’t last. The germination percentage may be significantly lower than that of improved varieties as well. Germination percentages of 90% or higher are desired.

Many farm stores will allow you to request a custom mix, often at no additional fee, which allows you to decide what varieties of each species you want, and in what mixture. This is well worth the time and energy. Our suggested horse pasture mix for central Kentucky can be found in Establishing Horse Pastures.

Tall Fescue

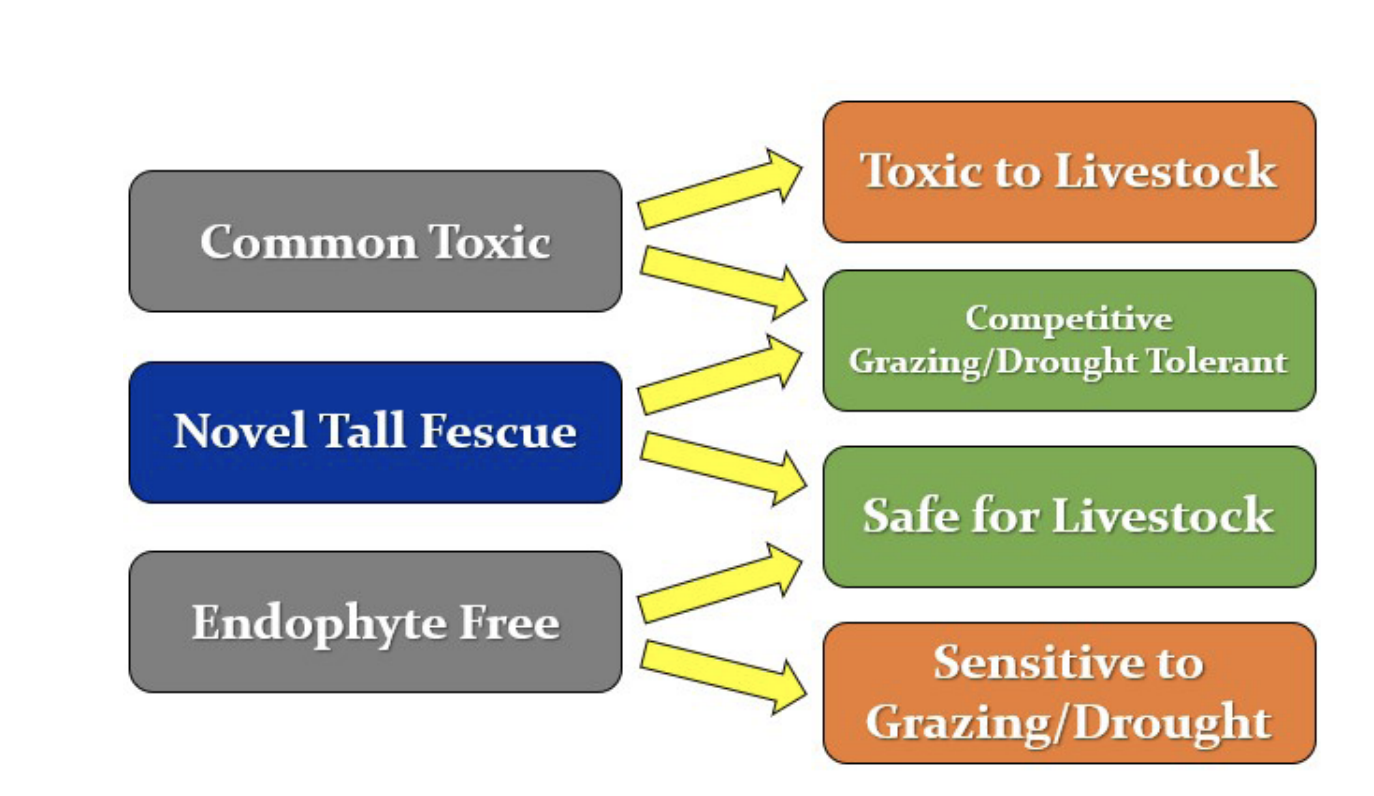

This cool season grass requires an added level of consideration. Because naturally occurring tall fescue is often infected with an endophyte toxic to broodmares and cattle, extensive research has gone into developing new, safe varieties of tall fescue. As a result, there are more varieties of tall fescue commercially available than most other grasses, and greater performance differences among them. There is also tremendous misunderstanding surrounding tall fescue varieties, so take the time to learn about each. Tall fescue can be one of three types: Endophyte free, Novel Endophyte infected or Toxic Endophyte infected. For your reference, the endophyte status of each variety is listed in the 2019 Tall Fescue and Bromegrass Report.

First, a bit of background on tall fescue. The endophyte is an internal fungus that was present in the original seed that was sown across most of Kentucky in the 1950s and 60s. This fungus interacts with the host tall fescue plant to produce many unique compounds, some that actually make the plant more drought and insect tolerant. But as the name ‘toxic endophyte’ suggests, some of these compounds are detrimental to livestock, especially pregnant mares.

Toxic endophyte tall fescue may also be called “KY31,” “KY31+” or wild type tall fescue. As stated previously, this combination of plant and toxic endophyte is problematic for livestock. In general, for horses, late term broodmares are those most impacted and can experience prolonged gestation, foaling difficulties and low milk production when grazing toxic endophyte tall fescue. Early term mares can occasional experience early term pregnancy loss. Generally speaking, stallions, geldings, growing horses and performance horses are not negatively affected by toxic endophyte tall fescue, although some physiological effects have been documented. If you do not have broodmares, you likely can tolerate this type of grass in your pastures. However, if you decide to kill out a pasture completely, go ahead and remove this from your mixture.

Traditional stands of KY31 have survived for decades, even under heavy grazing pressure, because of the presence of the toxic endophyte. However, generic KY31 seed is not monitored by either seed improvement agencies or commercial companies to ensure that the seed in the bag is actually the original KY31 genetics. Tests of generic KY 31 seed lots have found that the actual endophyte level varies considerably, and can be quite low (as low at 30%). Essentially this means that instead of getting the persistent (and toxic) tall fescue, you are actually buying endophyte free tall fescue. For this reason, if you do decide to purchase KY31 for its longevity benefits, be sure it is tested for infection before planting.

Endophyte free tall fescue was once a big deal, providing farm managers with the option to purchase tall fescue that was safe for all classes of livestock. But years later, that positive effect of the endophyte on the plant is painfully evident, as endophyte free stands rarely survive more than four to five years. Endophyte free varieties are safe for grazing, but do not have the longevity and typically will not survive long. For this reason, endophyte free varieties are not recommended.

Novel endophyte tall fescue is really the best of both worlds of persistence and lack of toxicity. This type of tall fescue contains a different endophyte, selected to give added persistence over endophyte free tall fescue but with none of the animal problems of toxic tall fescue. It may also be called a “friendly endophyte or beneficial endophyte.” The endophytes in these products were hand selected and the resulting varieties were rigorously tested for quality and safety to livestock before release. Some of this work has been done at UK, including grazing trials with pregnant mares. Because these products have had extensive research, development and testing, they are not cheap. But, if you are killing out and re-establishing a pasture, Novel endophyte tall fescue is absolutely the way to go and worth the added expense.

To ensure you are purchasing a tested and safe novel endophyte tall fescue, consider only those that have been certified by the Alliance for Grassland Renewal. This organization is a nonprofit collaboration of research institutions, seed companies and universities from across the southeastern U.S., including UK. If the seed lot meets its rigorous standards for endophyte purity and viability, it will have an additional seed tag or logo printed on the bag indicating it has been certified by the Alliance. You can learn more about the Alliance and novel tall fescue types on its website and by subscribing to its newsletter.

Summary

Selecting the best varieties for your pastures is a simple way to improve the chances your efforts of pasture renovation are successful for years to come. Just like purchasing proven bloodlines, selecting seed of improved varieties is well worth the investment and highly recommended. For any pasture seeding or renovation, be sure to follow these six steps to increase your chances of seeding success: 1) Apply any needed lime and fertilizer amendments. 2) Use high-quality seed of an improved variety. 3) Plant enough seed at the right time. 4) Use the best seeding method available. 5) Control competition. 6) Allow the immature seedlings to become established before grazing.

Krista Lea, MS, coordinator of the University of Kentucky’s Horse Pasture Evaluation Program, and Jimmy Henning, PhD, extension professor in the Department of Plant and Soil Sciences, provided this information.